Elon in his thirties

The past few weeks, looking deeply at Founders podcast and David Senra, considering plans for a “Founders podcast for great historical diplomats” (plan here), of the likely 50+ books Senra mentioned in interviews of his I listened to, one stood out that I was most keen to read cover to cover. Clip for 1-min:

“Elon is in a class of his own. In many cases, for a lot of the modern-day founders, there is a historical equivalent. There is even a Steve Jobs before Steve Jobs [Edwin Land]. There’s no Elon Musk before Elon. The reason I love this book Liftoff so much is because it’s the first six years of SpaceX. That’s it… [When reading] I’ll look up: how old are they [a book’s subject] when this is happening? That book is about Elon Musk when he’s 30–37. Me and you think about Elon now: world’s richest man, unbelievably powerful, tipping elections… He was age 30–37, and 90%+ of that book is him failing. They can’t get the rocket into orbit. They’re running out of money. He’s going through a divorce… It seems as though he’s essentially having his $180M from PayPal lit on fire.”

Despite being an Elon fan, I’d never even heard of this book. Not a sweeping biography like the Ashley Vance and Walter Isaacson biographies. Just a focused look at these six years.

I read it Thursday and Friday last week. Below are my highlights.

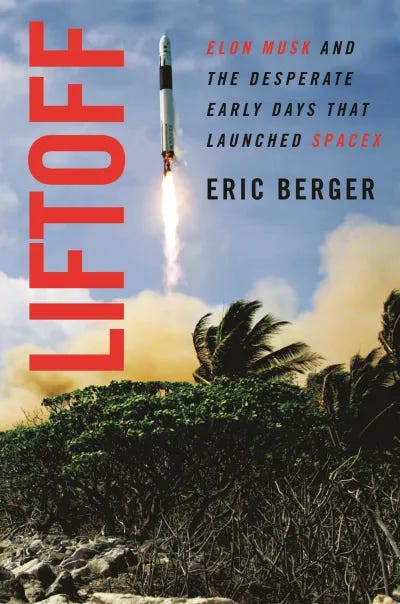

Liftoff: Elon Musk and the Desperate Early Days That Launched SpaceX

Elon Musk had a lot on his mind when I nudged his memories back to the tiny island of Omelek… Musk understands the significance of the Falcon 1 rocket to his life, and how its singular success spurred a transformational change across a number of fronts. Before this book, he had never consented to telling the story in full, or to allow an author free rein inside SpaceX to speak with employees about the company’s formative years. But Elon Musk wanted me to talk to everyone for this book. And he meant it.

Just before getting into…

I have no idea quite how serious Elon is with the America Party (a new third US political party Elon’s floated over the weekend – so urgent he sees the problem of the US debt spiral, and so dissatisfied he thus is with the Big Beautiful Bill and President Trump):

But President Trump hitting back at Elon saying “despite the fact that they [new third parties] have never succeeded in the United States”…

…Seems to me more likely to encourage than dissuade Elon. (Neither had reusable 🚀.)

As much as I enjoy Applied History and reasoning from precedent, as Senra says, Elon might be an exception to all previously enacted history.

I support President Trump on ~80% of things, but see this as very healthy democratic pressure on the administration to rein-in spending (which was heavily campaigned on, and upon which everything else relies). If I were a Republican Senator right now, I’d like to think I’d be taking a Rand Paul-like stance.

One can understand why Elon is so disgruntled:

And when looking at any US debt/deficit graph, I think Elon is undeniably right and that the Trump administration is not acting with nearly enough urgency.

Peter Thiel’s “#1 rule: Never bet against Elon”.

We’ll see if the America Party is a weekend media stunt, or if it actually turns into something. If the latter, perhaps the below highlights offer a window into what its early years might look like…

Introduction

The story of how SpaceX survived those lean, early years is a remarkable one. Many of the same people who made the Falcon 1 go remain at SpaceX today. Some have moved on. But all have stories about those early, formative years that remain mostly untold. The men and women who helped Musk bring SpaceX through its darkest days.

On recruitment and Elon’s psychology:

NASA paid him [Bjelde, a young engineer] a comfortable $60,000 a year, along with his tuition. SpaceX offered less. For a chance to work with a visionary, on an inspiring project with a mission he could embrace, Bjelde would have to eat a salary cut.

If anything, the doubts expressed at this meeting [initial plans for the private rocket company], and by some of his [Elon’s] confidants, energized him more.

He had cleared about $180 million from PayPal, and figured he could risk half of that on a rocket company, and still have plenty left over [for Tesla and SolarCity]. Musk brought the cash, and wanted his early employees to invest in sweat equity.

Thompson, with a young family, shared the same hesitation about leaving a comfortable position in the aerospace industry. During a phone call in late April, Musk sought to allay those concerns. Musk recognized what Thompson and Mueller were walking away from, so he put two years’ worth of salary for both engineers into an escrow account. That way, if Musk decided to prematurely pull the plug on the venture, they would still have a guaranteed income.

During the interview, Musk explained that he was paying for everything at SpaceX out of his pocket. And then he asked Reagan, “What’s the cheapest you would work for?” They haggled for a time, but eventually Musk agreed to meet Reagan’s asking price. He needed the help.

It was indeed scrappy:

the trio continued to meet in airport hotels.

Because they were spending his money, Musk gave employees an incentive to be frugal with it.

everybody knew everybody, and each employee pitched in as needed with other departments… It was definitely multiple hats, up to and including janitor.

Then someone, a new hire this week or a vice president the next, would take the only SpaceX company credit card down to the store, place the orders, and return to the company’s offices.

What Elon was like to work with:

These kinds of trips [abroad/to look at potential launch sites], of which there were many, helped Musk bond with his senior leaders. He could be difficult to work for, certainly. But his early hires could immediately see the benefits of working for someone who wanted to get things done and often made decisions on the spot.

Over the course of a single meeting Musk could be, at turns, hilarious, deadly serious, penetrating, harsh, reflective, and a stickler for the finest details of rocket science. But most of all, he channeled a preternatural force to move things forward. Elon Musk just wants to get shit done.

The [early] engineers sitting in those seats around the conference table had to possess a certain amount of mania, too. First they had to accept Musk’s ambitious, if not all-but-impossible vision. But it takes a rarer breed still who can sprint through thickets of technical problems as someone urges them on, faster and faster. One of Musk’s most valuable skills was his ability to determine whether someone would fit this mold. His people had to be brilliant.

Ten minutes later he returned with a contract. It was Saturday, November 1, at 5 P.M. Musk wanted his new vice president of machining to start work that evening. [😂]

He always made the most difficult decisions. He did not put off problems, but rather tackled the hardest ones first.

the quality she has come to admire most about Musk is his determined mindset to identify problems and devise solutions. “He looks at a problem and his reaction isn’t ‘Oh, that’s a shame’. His reaction is to go fix it. He’s extraordinary.”

There was still a lot of humor:

“You just really needed something to break up the constant push to be doing things a lot faster than what we were doing,” Altan said. “If you didn’t have that lighthearted outlook at SpaceX, it would have been a really tough time to survive in the early years.”

Great management question:

In meetings, Musk might ask his engineers to do something that, on the face of it, seemed absurd. When they protested that it was impossible, Musk would respond with a question designed to open their minds to the problem, and potential solutions. He would ask, “What would it take?”

“I’ve never met a man so laser focused on his vision for what he wanted,” she said of the experience. “He’s very intense, and he’s intimidating as hell.”

On eating costs and overheads, without revenue:

This placed SpaceX in a horrible position. While the Falcon 1 waited its turn, no one would compensate SpaceX for its expenses. The company got paid when it launched. By contrast, when the military awarded a national security launch contract to an Atlas or a Delta rocket, Lockheed and Boeing signed cost-plus agreements, where any delays were billed to the government, plus a fee. “Technically, we weren’t kicked out of Vandenberg,” Musk said. “We were just put on ice. The Air Force never said no, but they never said yes. This went on for six months. The resources were draining out of the company. Effectively, it was just like being starved.” Almost from the beginning of its existence, SpaceX had pinned its hopes on this launch site, with easy access to polar orbits, located only 150 miles from its factory. In the haste to build ground systems, SpaceX had invested $7 million in launch facilities at Vandenberg. There would be no reimbursement. Musk had to eat the loss. He still had funds remaining from his initial investment, but with a payroll of more than one hundred employees SpaceX had maybe another year. And now he had to stand there and take it when the Air Force told him to wait, perhaps indefinitely, to fly from Vandenberg.

They had to go and find a new launch site, and start again all over:

They had just worked themselves to exhaustion building one launch site. Now they would have to turn around and build a second one.

Despite these early setbacks, Koenigsmann had grown increasingly convinced SpaceX had taken the right approach to building a rocket.

Doing almost anything to hire the best, quickly:

Musk called Koenigsmann. Would he consider coming and working for a new rocket company? He would. With his characteristic forward style, Musk arranged an interview at Koenigsmann’s home in San Pedro.

Micro-manager?

Altan had hoped to sink into one of the private jet’s spacious leather seats to catch up on missed sleep, but instead Musk peppered him with questions. What, exactly, had happened? How had broken electronics ended up on his rocket? Ever detail oriented, Musk wanted precise answers, and detailed plans for what to do when they arrived in Kwaj. Altan slept not a wink.

Something that happens recurrently throughout the book: the team are about to do a critical launch, and Elon (on the day of the launch, which everyone is preoccupied with) starts grilling people on their thinking for next/future projects. No let up.

As ever, Musk’s mind bent toward the future. While Buzza and the launch conductor, Chris Thompson, worked through the countdown, Musk held a position at the back of the room on a platform. Throughout the countdown, Musk kept beckoning Thompson back to discuss materials for building the Falcon 5 rocket, his plan for a follow-up booster with five Merlin engines. Musk wanted more information on Thompson’s plans to order a special aluminum alloy for the Falcon 5 fuel tanks. At about T−30 minutes, Musk walked to Thompson’s console position and began a particularly heated conversation about why the materials had not yet been ordered. “We were right smack in the middle of a count, and he just wanted to have this deep, aggressive conversation about materials,” Thompson said. “I was absolutely dumbfounded that he was not even aware that we were trying to launch a rocket, and that I was the launch conductor, and responsible for basically calling out every single command that we’re going to run. It just blew me away.” After Musk walked off, Buzza turned to Thompson and asked, “What in the hell is going on?” In truth, this was just Musk being Musk, multitasking to the nth degree. Even in the middle of a critical countdown, he had the ability to simultaneously think about the company’s needs six months or a year into the future.

Dedication. A team member on Musk’s private plane:

he also watched the Musks carefully. While Kimbal played video games, his older brother spent much of the flight poring over books written about early rocket scientists and their efforts, such as the U.S. program under Wernher von Braun and the Soviet program under Sergei Korolev. Musk seemed intent to understand the mistakes they had made and learn from them. “I’m not surprised he has been successful,” Lawrence said. “He was clearly dedicated.”

He was able to be softer as a manager and uplifting in collective failure:

Musk wrote that the company would undertake a full analysis to determine exactly what had gone wrong. He hoped to try another launch within six months. As part of his note, Musk also offered some comforting perspective. Other iconic rockets, he noted, had failed often during early test launches, including the venerable European Ariane fleet, the Russian Soyuz and Proton boosters, the American Pegasus, and even the early Atlas rockets… “SpaceX is in this for the long haul and, come hell or high water, we are going to make this work.”

On first meeting Gwynne Shotwell, who ultimately become President/COO:

“Just come in and meet Elon.” The impromptu meeting might have lasted ten minutes, but during that time Shotwell came away impressed by Musk’s knowledge of the aerospace business. He seemed no dabbler, flush with internet cash and bored after a big Silicon Valley score. Rather, he had diagnosed the industry’s problems and identified a solution. Shotwell nodded along as Musk talked about his plans to bring down the cost of launch by building his own rocket engine and keeping development of other key components in-house. For Shotwell, who had worked for more than a decade in aerospace and knew well its lethargic pace, this made sense. “He was compelling—scary, but compelling,” Shotwell said.

And again – speed in recruiting the best:

Later that afternoon Musk decided that he should, indeed, hire someone full-time. He created a vice president of sales position and encouraged Shotwell to apply. The prospect of a new job had not been on Shotwell’s radar. After three years at Microcosm, using her mix of engineering and sales skills, she had grown the firm’s space systems business by a factor of ten. She enjoyed her job. Moreover, by the summer of 2002, Shotwell felt like she needed some stability in her life. Unlike most of the recent college graduates Musk was hiring to work day and night, Shotwell had a lot to balance in her personal life. Almost forty years old, she was in the midst of a divorce, with two young children to care for and a new condo to renovate. It would be good for the aerospace industry to have someone like Musk come in and shake things up. But did she want to disrupt her life as well? “It was a huge risk, and I almost decided not to go,” she said. “I think I probably annoyed the hell out of Elon because it took me so long.” In the end, opportunity called, and she answered. Her final decision came down to a simple calculation: “Look, I’m in this business,” Shotwell thought at the time. “And do I want this business to continue the way it is, or do I want it to go in the direction Elon wants to take it?” So she embraced both the challenge and the risk Musk offered her.

Getting straight to it:

During her first day at work, she [Shotwell] set about formulating a strategy to sell the Falcon 1 rocket to both the U.S. government as well as small satellite customers. Seated in the cubicle farm at 1310 East Grand, Shotwell wrote a plan of action for sales. Musk took one look at it and told her that he did not care about plans. Just get on with the job. “I was like, oh, OK, this is refreshing. I don’t have to write up a damn plan,” Shotwell recalled. Here was her first real taste of Musk’s management style. Don’t talk about doing things, just do things.

It’s notable to me that Elon didn’t himself do/oversee sales.

If you think there’s any merit to Myers-Briggs, Elon’s thought to be an INTJ (as am I).

Elon is obviously 10,000X+ more capable than any ordinary person – yet he’s still wary of not taking on things which are not natural strengths/energy-adders:

From the beginning, Shotwell understood the complex and evolving relationship between the Air Force, NASA, and private industry. Musk, however, was still learning about his new federal customers. In addition to selling rockets, part of Shotwell’s job became managing relations between the company, her boss, and the U.S. government.

Using doubters as fuel:

Teets was generally supportive of the start-up’s intentions, but he had seen this kind of presentation before. “I remember him putting his hand on Elon’s back, almost hugging him, and saying, ‘Son, this is much harder than you think it is. It’s never going to work,’” Shotwell said. At this remark, Musk’s back straightened, and he got this look in his eye that Shotwell could easily read. If Musk had harbored doubts about completing the Falcon 1 project before the meeting, Teets’s paternalistic gesture had hardened his resolve. “You’ve just changed his mind,” Shotwell thought about Teets, and the effect of his words on Musk. “He’s going to make sure you regret the moment you said that.”

Explaining sensible design, development and procurement to government is just hard:

The company’s iterative design philosophy was new to many government officials working in aerospace, and accustomed to stable designs and slow-moving projects. “Keeping up with that, and explaining to customers why we had a different approach to this or that, was a challenge,” Shotwell said. Patiently, she would describe the company’s method of making mistakes early in the design process, so it could weed those errors out of the final product. “These are government customers, so even though they wanted to move quickly, things changing as rapidly as they did still did not provide a lot of comfort. That was one of the hardest things I’ve had to work on for almost my entire career at SpaceX.”

Speed:

During meetings, Musk will make snap decisions. This is one of the keys that enables SpaceX to move so quickly.

Building on spec, and anticipating future need:

In the case of the Falcon 1, Musk needed government customers to start placing orders for launches. This was how he believed SpaceX would one day become profitable. Beyond the small D.A.R.P.A. Falcon program, however, the government had not identified a small satellite launch need, nor had it issued contracts to build one. Rather, Musk anticipated such a need and self-funded development of a rocket to serve both commercial and government customers. He built the rocket on spec.

The freedoms this allows, and the trade-off:

“When the government is hiring you to design, develop, build, and operate a thing, they’re the customer,” Shotwell said. “They’re paying for it. They get to have their hands in the design. The decisions. They’re covering the whole thing. But no one was paying us for design or development. They were paying us for flights.” … This offered an advantage in that SpaceX could build the rocket that Musk and his engineers wanted to—but it came with a big downside. Unless Shotwell sold a multitude of launch contracts, the company would die.

Establishment figures had extremely little interest:

“Most of the aerospace people wouldn’t even talk to us,” he said. “Most of the time they didn’t know who I was. And if they did know, I was some internet guy, so I was probably going to fail.”

Establishment types are quite happy to see you fail:

there was no shortage of competitors in the aerospace community just waiting to see another “commercial space” company fail, so the large launch companies could continue to collect lucrative government contracts without much competition.

Elon went in swinging:

Almost from the beginning, then, SpaceX had to battle for its existence. One of the secrets of Musk and Shotwell’s success is they did not kowtow to the existing order of large companies and government agencies. If they had to sue the government, they would. To fight back Musk would use everything at his disposal. Within its first three years, SpaceX had sued three of its biggest rivals in the launch industry, gone against the Air Force with the proposed United Launch Alliance merger, and protested a NASA contract. Elon Musk was not walking on eggshells on the way to orbit. He was breaking a lot of eggs… This, of course, made life difficult for Shotwell, who would meet with competitors at space conferences and have to smooth ruffled relationships with government officials.

One likely would have bet against success four years in:

There’s an old joke that goes: if you want to become a millionaire, start out as a billionaire, and found a rocket company. Musk was not a billionaire before he founded SpaceX, but four years into the venture it certainly had the look of a big money loser.

But then, they got a break…

As the summer of 2006 dragged on [four years into the company], SpaceX and the other finalists waited to find out who would receive the lucrative contracts to design their cargo delivery vehicles. The call from NASA finally came in August. Shotwell was upstairs, at the company headquarters in El Segundo, with Musk. After hanging up, they called an impromptu staff meeting out on the factory floor, where work briefly stopped on the next Falcon 1 rocket. Musk stood in the kitchen as the employees gathered around. His speech was short. “Well,” he said. “We fucking won.” SpaceX had won big in a couple of critical ways. First, there was the money. The contract value of $278 million would allow Musk to accelerate his plans to build the big orbital rocket, and ensure the company’s future while his team worked out its problems with the Falcon 1 vehicle. With the funds, SpaceX could also move into its larger, now iconic headquarters in Hawthorne. Perhaps most significant, with the contract award NASA had endorsed the company. “That was really important,” Shotwell said. “We were a little company. We were jackasses at that time. We blew up a rocket in March of that year. From my perspective, NASA was acknowledging that even though we had a failure on Falcon 1, they felt like we had the right attitude.”

Team members navigating so difficult a manager:

“As far as working with Elon, I think Tom and Hans and I were able to walk that middle line.” The middle line being that Musk listened to ideas. He encouraged debate. He empowered his senior employees funding and authority. But always, he had the final say.

“I think that having people like Tom Mueller and Hans Koenigsmann and Chris Thompson and myself was important. We brought some heritage aerospace experience, but also were willing to be totally molded by Elon to change our thinking.”

Musk was there every step of the way. “Having Elon, it makes things a lot simpler because he is super involved, he makes those difficult decisions,” she said. “When those times came, he would step in and make those decisions like, ‘Are we going or not? What are we doing here?’ And he’s always kept us focused on that vision. He never would relieve us of any little detailed duties, but he would always make sure that we would come out and look at the bigger picture. I think that was really important to keep that focus.”

Such freedom on display:

“That’s the thing about Elon, he was willing to spend money to try things,” Kassouf said. “And that’s so different. Go to Boeing, and you spend money to try and figure out what your liabilities are going to be before you try anything. But Elon is like, sure, try it. If it doesn’t work we can either sell it back, or it goes into our lessons-learned pile.”

Three flights to get to orbit:

Less than five years after its founding, the company had climbed above Earth’s atmosphere. SpaceX’s next step was clear—orbit. “We had always talked about needing three flights to get to orbit,” Buzza said.

Encouragement, following their second big attempt:

Musk, too, was feeling better about his rocket company. A few days after the flight, he said publicly that the mission represented a “large step forward” for SpaceX.

A hilarious point: the team had drawn up a “top ten” list of risks, and problem-solved all steps they needed to take to mitigate them. The risk that proved to be the ultimate problem (preventing launch two getting all the way to orbit) had been risk #11:

As a handful of simulations had predicted, liquid oxygen in the upper-stage tank had begun sloshing around several minutes after launch, inducing a fatal oscillation. The problem they had known about, discussed in detail, and ultimately dismissed as the eleventh highest avionics risk took down their rocket. “Now,” Musk says, “I ask for the eleven top risks. Always go to eleven.”

No compromise:

During the early 1990s, in an effort to become more efficient and businesslike, NASA adopted a “Faster, Better, Cheaper” approach to space science missions. By the time SpaceX was founded, however, several high-profile NASA missions had employed this philosophy and failed. For any aerospace project, the joke became that you could never have all three, that a mission could never be faster, better, and cheaper. You had to pick two. But in pushing for high-performing, safe, and cheap rockets, Musk was not picking two. He was picking three. He wanted SpaceX to move fast, build better rockets, and sell them cheaply.

“Delete” things (I consider this applies to system complexity too, not just gravity):

To build a better rocket, SpaceX had to limit its overall mass. So Musk fought to reduce weight. If he gave awards for rocket design, they would go to engineers who undesign things, those who remove mass. All too often, engineers want to add a part or a component just in case it might be needed during a contingency. Pretty soon, a rocket becomes fettered with widgets.

This happens gradually – one needs to fight it at every step:

“Inevitably with rockets, when you’re trying to get into orbit, things look great in the beginning,” he said. “There’s lots of payload capacity. But then you lose a little performance here. Just give up a little bit of ISP [efficiency] there. Now you’re a piece-of-shit rocket. You get chiseled away by 1 percent or 2 percent at a time. That’s how it works.”

Elon’s pent up frustration from taking on such a big challenge:

“Just FYI. It’s not like other rocket scientists were huge idiots who wanted to throw their rockets away all the time. It’s fucking hard to make something like this. One of the hardest engineering problems known to man is making a reusable orbital rocket. Nobody has succeeded. For a good reason. Our gravity is a bit heavy. On Mars this would be no problem. Moon, piece of cake. On Earth, fucking hard. Just barely possible. It’s stupidly difficult to have a fully reusable orbital system. It would be one of the biggest breakthroughs in the history of humanity. That’s why it’s hard. Why does this hurt my brain? It’s because of that. Really, we’re just a bunch of monkeys. How did we even get this far? It beats me. We were swinging through the trees, eating bananas not long ago.”

The best way to get over personnel tensions/friction/grievances is future success:

“My engine caught on fire, so I was in deep shit,” Mueller said. “For the whole year between the first two launches, Elon and I were not good.” … When the Kestrel engine came alive on Flight Two, Mueller leaped out of his chair and cheered. Musk joined him, and they hugged and whooped together. In the span of a single moment, all was forgiven… The rekindled trust was a good thing, as Mueller and Musk had a big task ahead of them.

Elon often had wacky ideas:

Then Musk had an idea. Perhaps, if they applied epoxy to the chambers, the sticky, glue-like material would seep into the cracks, and then cure, solving the problem. It was a Hail Mary. Mueller doubted the epoxy would stick to the ablative material, mixing about as well as oil and water. But sometimes Musk’s crazy ideas worked.

Other times, however, they didn’t:

It didn’t take long, after pressures began to rise, for the epoxy to come undone. Soon, it flew off the interior walls of the chamber, revealing the cracks beneath. Musk had been wrong. But the filthy and exhausted engineers and technicians working with him all night did not begrudge Musk for keeping them at a task that proved fruitless. Rather, his willingness to jump into the fray, and get his hands dirty by their sides, won him admiration as a leader.

The sacrifice made by early team members, and their schedule:

Initially, Buzza had thought that flying to and from Texas on Musk’s jet was glamorous. But over time, the novelty wore off. It became grueling, especially for Mueller and Buzza, who had young children. They lived dual lives. For ten days, they would work twelve- to fourteen-hour shifts in McGregor before flying back to California, where typically they would have Thursday through Sunday afternoon off. Then they would get back on Musk’s jet for the return trip to Texas. For nearly two years, every other Sunday evening, Hollman would drive to Buzza’s house in Seal Beach, picking him up on the way to the private airfield in Long Beach.

Giving more than an earful to faulty suppliers:

Musk and Thompson flew out to Texas that night to do a postmortem. The problem, they felt, was with the vehicle’s welds. They were poorly done. The more they looked at the fuel tanks, the angrier Musk and Thompson got. A few years earlier, they had been impressed during their visit to Spincraft in Wisconsin, when Musk had burned his hands on the Holiday Inn Express toaster. But when Musk and Thompson flew to the company’s headquarters in early 2005, they were no longer impressed. Walking into the Spincraft welding shop, Musk looked at the general manager, Dave Schmitz, and around the rest of the shop, Thompson remembers. Then Musk gave vent to his anger at the top of his lungs. “You guys are fucking me and it doesn’t fucking feel good,” Musk bellowed. “And I don’t like getting fucked.” The entire manufacturing facility ground to a stop. “You could hear a pin drop when he screamed that out. I mean, people stopped dead in their tracks, including all of us,” Thompson said. But it got the message across.

A particularly good story of a young person landing an early internship:

it was not in Dunn’s nature to give up easily. He earnestly pressed his case, saying, “Mr. Mueller, this is my dream. This is exactly what I want to do with my life. If there’s any question that you could ask me, anything I could do to demonstrate that I’m the right person for this, just let me know.”

Having said his piece, Dunn paused and waited expectantly. “OK,” Mueller told Dunn. “You can come out to Texas this summer.”

(Dunn went on to take a very high-level role in the company at an extremely young age.)

Finances again grew extremely tight:

The company had not reached the financial breaking point yet, thanks to NASA’s funding in 2006. But a company founded to profit from launching payloads into space had to, at some point, begin launching them safely into orbit.

Having slightly odd/unexpected initial customers is okay:

Finally, SpaceX had its first truly commercial payload, the “Explorers” mission from Celestis, which sends cremated remains into space. On this flight the company gathered the remains of paying customers… None of these were multi-million-dollar satellites, but in a single launch SpaceX was hosting payloads from its three most important customers—military space, civil space, and commercial space.

Flight Three

Musk’s funds, not unlike his patience, had limits. “The crazy thing is that I originally budgeted for three attempts,” Musk said. “And frankly, I thought that if we couldn’t get this thing to orbit in three failures, we deserved to die. That was my going-in proposition.”

But it did fail, again:

In the immediate aftermath of the failure, no one was making that assumption [the company could keep going] back on Kwaj. One of the engineers in the control room alongside Dunn, Bulent Altan, rode back to Macy’s with his mind spinning like the tires on his bike. Had he and his wife moved from the Bay Area to Los Angeles and sacrificed so much for this? Would there be another attempt? Did Elon have any money left? Would there still be a SpaceX in a few days?

They mourned what had happened. The first two flights had felt like a progression, from an early failure to a very late one just before reaching orbit. This third failure felt like a regression. And if the company was not moving forward, where was it going? “Before that flight I think we all thought, ‘This is the one, man. We got so far on Flight Two. We got this,’” Flo Li said. “That one was, I would say, the most heartbreaking flight for all of us. I think I felt the most devastated after that one just because we had gotten so far in Flight Two. I think we really thought that we had this in the bag for Flight Three, and then to fail in the manner which we did, that one was rough.”

“Flight Three was devastating,” Chinnery said. “Early on, Elon had said he would cover the first three flights. He wanted to give it a good college try. But how long would he stay in the game? Three failures is a lot of failures. “Hardly anyone survives that in the aerospace world.”

Major doubt – across the company:

It was bad luck, to be sure. But SpaceX had run through a lot of bad luck over the years, and bad luck only got you so far as an excuse. Maybe they just weren’t all that good. Certainly, there could be no denying the company’s dismal record. SpaceX had launched three times, with Koenigsmann playing an important part in all three missions. They struck out on all three. Musk had held up his end of the bargain, making good on his promise of providing seed funding, and supporting the company for three launch attempts. Now, with failure after failure, Koenigsmann worried that Musk might throw his dwindling resources and time into Tesla or another venture. He could hardly blame the entrepreneur.

It all was unraveling. He’d tried to change the world, and the world resisted.

Elon in a dire position:

Then it was Musk’s turn [to speak]. No one quite knew what the boss would say. Musk felt as crestfallen as the rest of his employees. Worse, even. He had bet a lot on SpaceX, in time and money and emotional toil, with little return. Now, his personal fortune was running dry. He’d invested everything in SpaceX and Tesla. Beyond money, his personal life was falling apart.

Everything is against him:

“At that time I had to allocate a lot of capital to Tesla and SolarCity, so I was out of money,” Musk said. “We had three failures under our belt. So it’s pretty hard to go raise money. The recession is starting to hit. The Tesla financing round that we tried to raise that summer had failed. I got divorced. I didn’t even have a house. My ex-wife had the house. So it was a shitty summer.” Musk really had put all of his net worth into his rocket and electric car ventures, and in August 2008, he had almost nothing to show for it. His rocket company had produced a litany of failures. Tesla was equally cash-strapped, only just beginning to sell its first product.

It was a hell of a time to be running a single, cash-hungry start-up business, let alone two. The Great Recession, precipitated by a housing bubble and subprime mortgage crisis, technically began in the United States at the end of 2007 but began to swamp the wider economy in 2008.

How Elon addressed the SpaceX team:

As Musk looked around the conference room in early August, he saw a chance for salvation. He had a good team. He personally hired all of these people, judging them to be smart, innovative, and willing to give their all. He had driven them hard, so very hard. They had made mistakes. But they were dedicated, and had put their souls into SpaceX. So in this dark hour, Musk chose not to play the blame game. Certainly, he could dish out brutally honest feedback, crushing feelings without regard. Instead he rallied the team with an inspiring speech. As bad as Flight Three had gone, he wanted to give his people one final swing. Outside that room, in the factory, they had the parts for a final Falcon 1 rocket. Build it, he said. And then fly it. What they did not have was much time.

“He collected everyone in the room and said we have another rocket, get your shit together, and go back to the island and launch it in six weeks.” After Musk’s staff meeting, his employees realized they were playing for everything. If their final rocket launched safely into orbit, the company would have a chance to survive. Success would give Musk an answer for the company’s growing legion of doubters. Shotwell, too, could stop trying to rationalize failure to potential customers and perhaps begin to ink new contracts.

Six weeks Four weeks:

On Friday, September 5, she presented the timeline to Buzza, her immediate supervisor. Back in Hawthorne, he and Thompson shared it with Musk. “Elon saw that and went off the frickin’ deep end,” Thompson said. Six weeks was too long. SpaceX didn’t have six weeks. Realistically, SpaceX did not even have a month before its funding ran out.

The team stepped up:

“I can’t believe we disassembled an entire stage and reassembled an entire stage in the course of a week. I don’t think I could have imagined that.” They had broken virtually every rule in aerospace to pull the first stage together, but because of these heroics on Omelek, SpaceX still had one last shot at survival.

*The story of things going wrong ahead of Flight Four is so insane/crazy/nail-biting I cannot in any way do justice to it in highlights. For sheer narrative, if there’s one chapter of the book to read in full, make it Chapter 9.* Continuing…

“I was stressed out of my mind,” Musk said of the countdown. “Super tense.”

There was a lot more on the line than one company:

Giger worried about letting family and friends down if the Falcon 1 failed. He worried about letting the country down in a sense. If SpaceX went under, it would take a lot of the nascent aspirations of the new space movement with it.

They pulled it off. It was a miraculous success:

As late afternoon turned into evening, and evening turned into night, the California parties swelled. Some employees had gone to the Tavern on Main, some to the Purple Orchid, which was where the party went latest that night. The drinks were put on corporate cards. After Musk finished a news conference and interviews, he made an appearance at both of the boisterous parties. When he walked through the door at each one, the assembled employees went nuts. Through his singular leadership, they had done a great thing. And they loved him for it.

Overlaying all of this was the sheer exhaustion of working nonstop between Flights Three and Four. Somehow, in the darkest of moments, in the most distant of tropical outposts, with the final chance before them, they had pulled together. They all knew that, very easily, they could have been drinking away their sorrows that night, making final goodbyes before they dispersed to other rocket companies, into academia, or elsewhere. Instead, they toasted to their shared experiences and a bright future.

Musk called the Falcon 1’s brilliant flight “the culmination of a dream.”

They still weren’t out of the woods:

Even as SpaceX achieved success, both of Musk’s major companies spiraled toward bankruptcy. That fall he had about $30 million cash left. [Which would be burned through rapidly with overheads of the companies.]

“It was not like we had a bunch of customers lined up,” Musk said. “We had the Malaysians, and there was just not a good runway of stuff to do after that.

All of a sudden, it appeared as though SpaceX just might be able to build rockets. Still, Musk fretted about how his company’s desperate finances must look to NASA as his personal wealth dried up amid the recession.

But, just in time, a contract and financing came in:

After the call, Musk asked Shotwell to immediately sign whatever deal NASA offered. He harbored a niggling fear the space agency might take the contract back. Two days later, on Christmas Eve, at 6 P.M., Tesla closed a financing round that provided the strapped automobile company with six months of funding. At a stroke, his two seemingly doomed companies were saved.

“It felt like I had been taken out to the firing squad, and been blindfolded,” Musk said. “Then they fired the guns, which went click. No bullets came out. And then they let you free. Sure, it feels great. But you’re pretty fucking nervous.”

As soon as things had stabilized, Elon immediately multiplied their ambition:

A few weeks later, everything changed. Musk called a meeting of the Falcon 1 team, and told them, without preamble, that the booster had flown for the last time. “That was tough for a lot of us that had worked the Falcon 1 missions,” Chinnery said. “We spent so much effort and time on making that program successful, and to move on like that was classic Elon. He was very focused on what he wanted, and Falcon 1 wasn’t in the plan beyond just learning how to do it.” Once they got beyond their initial shock, however, the Falcon 1 team accepted the wisdom of Musk’s decision. It meant less work, as they would not have to spend time developing, testing, and building the Falcon 1e. With the extra hours, they could focus on Falcon 9 and Dragon, which now represented the future.

On talent conglomeration, and taking every opportunity for top-level recruitment:

The Swiss-born scientist had helped build and run a highly regarded graduate program in space engineering at the University of Michigan, and in the spring of 2010 Aviation Week asked Zurbuchen to write about talent development. As part of this exercise, Zurbuchen made a list of his ten best students based on academics, leadership, and entrepreneurial performance during the previous decade, and researched where they had ended up. To his surprise, half of the students worked not for the industry’s leading companies, but at SpaceX. The results blew him away. “That was before SpaceX was successful,” said Zurbuchen, who in 2016 became the chief of science exploration at NASA. “So I interviewed these former students and asked, ‘Why did you go there?’ They went there because they believed. Many of them took pay cuts. But they believed in the mission.” In his article for the aerospace publication, Zurbuchen wrote about how SpaceX had succeeded in the battle for talent with an inspiring goal. “I was a little bit nervous about betting on the immediate success of Falcon 9,” he wrote. “But in the long run, talent wins over experience and an entrepreneurial culture over heritage.”

Musk suddenly focused on the scientist with his characteristic, arresting stare. The pleasantries, such as they were, had ended. Musk asked a single question: Who were the other five students? “I realized that was what the whole meeting was about,” Zurbuchen said. “The meeting was not about me. He wanted to recruit them. He wanted the other five.”

When he [Zurbuchen] spoke with engineering peers at places like the Massachusetts Institute of Technology or the University of Southern California, he heard similar things. SpaceX had juice with their students, too: the freedom to innovate and resources to go fast summoned the best engineers in the land.

“Elon’s primary capability is to evaluate people quickly and pick the right people. Yah? He is really good at that.”

Establishment forces (including Senators in the state you’re bringing prosperity to) will remain against you:

political space leaders on Capitol Hill, allied with the existing aerospace power brokers, offered a muted response. The senior senator from Texas, Kay Bailey Hutchison, said, “Make no mistake, even this modest success is more than a year behind schedule, and the project deadlines of other private space companies continue to slip as well.” Such a tepid reaction is remarkable given that SpaceX had established the large, and growing, McGregor test facility in Hutchison’s home state.

SpaceX has changed the paradigm:

Today it is normal for SpaceX to launch rockets, catch them on land and at sea, and fly them again a couple of months later. In fewer than three years, the paradigm has shifted entirely. Whereas it once seemed novel to reuse a rocket, now it seems almost wasteful to throw them away. The company’s competitors initially scoffed at the notion of launching a rocket vertically, landing it vertically, and then flying again within a few months. Now they’re scrambling to catch up.

SpaceX legitimized the new space ethos of lowering the cost of access to space. It has shown that private companies and private capital, working alongside the government, can do amazing things in space.

19 years [now 23] and counting:

During an interview in early 2020, his [Elon’s] mind drifted back to that first impulse to get into the space business. He remembered a gray, rainy day on the Long Island Expressway with his friend Adeo Ressi, and later his frustration upon visiting NASA’s website and finding no plans. He could not understand why humans had remained stuck in low-Earth orbit since Apollo. And so he made a life-changing decision to commit himself to the goal of Mars, a commitment that has grown stronger over time. “That’s nineteen years ago, and we’re still not on Mars,” he said. “Not even close,” I replied. “Yeah,” he agreed. “Not even close. It’s a goddamn outrage.” This is the passion that fires Elon Musk, and impels him to drive his teams forward every single day. Decisions in his world come down to a simple calculus: Will this get humans to Mars sooner, or not? Little else matters in his mind. Though we are not yet close to Mars, we are leaps and bounds closer today than ever before. Musk’s first step was to bring down the cost of launch. Against all odds, he has done so. Now his company, with Musk’s constant urging and the accumulated knowledge of the last twenty years, is building the Starship vehicle to one day carry settlers to Mars.

Speed of progress:

This brutal devotion to speed got results. The first Falcon 1 launch attempt came a mere three years and ten months after Musk started SpaceX. The company reached “space” in four years and ten months. It made orbit in six years and four months. It did all of this starting with just three employees, limited government funding, and building a rocket from scratch with mostly in-house components for the engine and rocket.

Blue Origin, SpaceX’s most prominent new space competitor, was actually founded earlier, in 2000. It has taken a more stepwise approach, but for all of Jeff Bezos’s money has yet to launch a rocket into orbit after twenty years. [This written in 2021. Blue Origin now has, in January 2025, taking 25 years.]

Musk’s in-your-face management style came with benefits. He empowered his people to do things that would have required committees and paperwork and reviews at other companies. At SpaceX, if they could convince the company’s chief engineer of something, they also earned approval from the chief financial officer, as they were one and the same.

Doing things in parallel:

as ever, Musk remains the dominant driver behind the acceleration. While trying to get Falcon 1 flying, he wanted specs for the Falcon 5. Then his small company took on the challenge of building both the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon simultaneously.

for someone like Musk who sees only a narrow window to execute his sweeping vision, there is no other way.