“Belligerent for peace”: 12 lessons from Presidential Envoy for Special Missions, Ric Grenell

What’s the coolest job title in President Trump’s incoming Administration? For those equally fascinated by diplomacy and geopolitics, co-leadership of DOGE places second to the newly created “Presidential Envoy for Special Missions” announced last Saturday.

Having read Jared Kushner’s excellent Breaking History last summer, Ric was on my radar. But I didn’t know nearly as much about him as I should have, given my interest. Over the past few days, this has been corrected. I’ve been on a tear through Ric’s interviews and speeches, nodding vigorously with his advocated blend of diplomacy and deterrence.

Now less than a month to go until the incoming Administration takes office, what are the principles underpinning the thinking of President-elect Trump’s roving diplomatic stuntman?

1) Stopping wars is a non-negotiable

“President Trump is absolutely going to bring peace. He is somebody who is concentrated on peace; he doesn’t understand why we’re doing war.

We have to do the hard work of meeting with people, listening, and working towards peace. Diplomacy is tough. When you hear ‘peace through strength’, that’s a celebration of the State Department and diplomacy. It is a win for peace. It’s not a win for the Pentagon. My friends at the Pentagon like to pretend ‘peace through strength’ is their win. It’s a win for diplomacy – and that is not an easy task.

We have too much easy talk in Washington. Every time there’s a problem around the world, we send in the Pentagon. We can’t do that. We have to have powerful diplomacy. We have to have people on the front lines constantly working and listening.

What I can promise you that you are going to get from the Trump Administration is an open door to talk about these issues. We are going to listen, and we are going to talk. And we are going to discuss solutions. President Trump will absolutely stop these wars. It will be his non-negotiable.”

2) Implementation is imperative

The Russians signed Minsk. I don’t know if they ever really wanted to implement it. But one lesson I learned from the [2020] Kosovo-Serbia negotiations is that the person who does the negotiations, who looks at both sides, and tries to pull in both sides to say, ‘I need you to move this way, and I need you [the other side] to move this way’ – the person who does that knows the vulnerabilities, and where they [respectively] didn’t quite want to go. And so the most important part, when you finally get two sides to come together to agree on something, is the follow up and holding them to account. The people that need to do that are the ones who negotiated – because they know where the weaknesses are.

You have to be able to use the carrots and sticks in that instance. Remind them why they signed: ‘We know you don’t love moving this way, we know you don’t love making this concession, but it’s really important to do so.’

I would say the failures of Minsk were we didn’t have any follow up. Once it was signed, a whole bunch of people celebrated and moved on. That would be different under a Trump Administration. There would be absolute holding people to their commitments.

This echoes everything I’ve learned over the past several years from Dominic Cummings, who I worked with in 10 Downing Street, on the need for project management in government. Dom talking about this in heart-warmingly colourful language (clip for 3 minutes):

I saw (and had a small role in helping) Dominic do this. Ric is going to need a team to help ensure the sanctity of agreements reached. And with the unique role of a roving brief across conflicts/regions, a big operational question he is surely in the midst of figuring out is: how to oversee creative deal-making and deal-enforcement? How to structure a team that’s capable of doing both, so that the triumph of a signature one week in Korea is being stuck to when off negotiating in Venezuela the next? As Ric notes, this is a very big challenge:

In my years of diplomacy, and watching how we have agreements… I think most people agree that [on Minsk 1 and Minsk 2] there wasn’t a mechanism to hold Russia accountable… We’ve got to have a tougher mechanism to hold them to account. Maybe that’s a sliding scale of sanctions relief or whatever the carrot is.

But what I’ve learned about diplomacy, especially in Kosovo and Serbia, is that once you can get parties to see a vision, and to say ‘Oh gosh, I don’t want to do this but, maybe the pluses outweigh the minuses’ – and you know exactly where they are uncomfortable on each point – that’s when diplomacy starts. It’s not once it’s signed, then you’re done, and you just hope both sides go and implement it. You’ve got to hold their feet to the fire. You’ve got to have a team that reminds them why they’ve signed it. Remember all the parts of that agreement where they were uncomfortable and help them get through it. I think *the tough part starts as soon as you’ve signed the agreement*. And that’s not what happened on Minsk 1 and Minsk 2. There was a collective sigh of relief. There was a jovial moment and people were congratulating each other. And [they] just thought: let’s hope everybody implements it. I think that’s the wrong way to look at it. I certainly learned that with our agreements in Kosovo-Serbia. I wish, after we made our big agreement, there would have been more people holding both sides to account.

The Trump team was now gone, the Biden team came in and I was pleased that they embraced all four agreements as US policy. They said ‘these are great agreements. They should be implemented.’ But there was never a team to push them.

Thus, enforcement desirably should be something that ought to last beyond any one Administration.

3) Balance diplomacy and deterrence

1) I’m a diplomat. I feel very strongly that if I and other diplomats fail, that we have to transfer the file over to the Pentagon, and the Pentagon doesn’t negotiate. They implement. And so it’s really important to get it right. And that is why I believe diplomats cannot be wimpy. If you are there, on the front lines to avoid war, and to avoid military action, you better have some really tough diplomats. Not ones who are sitting in the background and having dinners and having a really good time in the country they are assigned to.

If you are there to avoid war, you have got a huge responsibility, and you’ve got to be really tough. And you better be Johnny-on-the-spot when it comes to using information to push and prod and find solutions. So I feel very much like I am on the front lines of avoiding war.

2) I’m proud to work for President Trump, because there is a difference between a threat of military action and a credible threat of military action. And make no mistake, President Trump has a threat that is credible. And because of that, he makes my job easier. Because when I am sitting across the table and I am pushing on these issues diplomatically, there is an assumption on the other side of the table that we better get this right, because we don’t want to transfer it to the Pentagon.

3) Very early on, I liked how President Trump viewed using diplomacy, talks and military action. He wants to avoid it [military action]. He understands that there are some serious issues that come with it. But he is also, as he showed us in Syria [2017-18], not afraid to do it. And I think the balance that he has – the angst that he has to use military force, and yet the resolve that he sees when he has to use it – is the perfect balance. I have confidence in the President’s ability to weigh all these issues and say, ‘I want to do everything I can to avoid war, but I have to make sure that there isn’t a message that’s sent that we aren’t watching.

On not giving up:

I firmly believe that diplomats should be at the forefront of pushing and prodding and demanding talks, and demanding that we have a table to air our grievances on.

Even if we’re planning to bomb, if the Department of Defense is ready to attack, I would hope that we have brave diplomats who are saying, ‘Wait a minute, I’ve got one more chance, let’s sit down, let’s try the diplomacy thing.’

I get hit constantly: ‘Oh, you’re undiplomatic/you’re too tough.’ But that’s what you want in a diplomat! You want someone who’s working hard to avoid war – through talk, through pushing and prodding. Rather than transferring the file over and having a problem solved through military action.

The Washington types are trapped into this idea that every time there’s a crisis, we’re supposed to send US troops – men and women on the ground. And that’s what we’re rushing to. I don’t know where we went wrong, but we’ve shoved the State Department off. They don’t get to do any serious diplomacy. And every time we have an Ambassador with muscle, they kind of mock that person… It’s almost like you’re supposed to be this weak person if you work at the State Department. My view is, if you want to avoid war, then you better have a very strong State Department, with diplomats who really know how to negotiate creatively. Because if we fail at the State Department, if we fail in our conversations across the table, then what we do is we send that file of a crisis over to the Pentagon – and they don’t negotiate.

You want MEAN diplomats:

You have to have a very tough, mean, Secretary of State. Right now [in Tony Blinken] we have a Secretary of State who will tell you that culinary diplomacy is how everything starts. And if you look at his social media feed, he is doing things that make you think, ‘Do you not realise that there are two wars?’

We heard from the Biden team, including from Antony Blinken, for at least 30 days before the Ukraine war, ‘The Russians are coming, the Russians are going to invade.’ I find it to be really immoral that the Secretary of State, who has his own plane, when he heard absolutely ‘the Russians are coming to invade Ukraine, we know they are coming, we have evidence…’ Why didn’t he get on the plane, go and gather all the Foreign Ministers in Europe, and get to Moscow and say: NO.

When you know that there’s a crisis, you’ve got to be there to solve it. But you look and Blinken goes every once in a while to the region and has another meeting, and then it’s a failure. I just feel like we’ve got to have somebody who’s much more direct, who talks about the consequences, and I want to see more action when it comes to peace deals and trying to solve things peacefully.

There’s no one who is being belligerent about a peace plan – and we need that.

Two strong voices in the Oval Office:

I believe that the President of the United States, in the Oval Office, when making big decisions – like hundreds of billions of dollars of American taxpayer money going to a foreign country – when you’re making those decisions, you need to have two strong voices in front of you:

1) A Secretary of Defense who does not negotiate – and is fully prepared to do whatever is needed.

2) But the President of the United States also needs a top diplomat who will say ‘Not yet, we’re not doing this yet, we still have diplomatic things to do’… And I’m sorry to tell you, through the entire [first] Trump Administration, the Democrats made fun of tough diplomacy. ‘You can’t be mean to our allies like that. You’re so mean.’ I have to say to you: you better have a SOB diplomat if you want to avoid war.

Of course you need the Pentagon behind you. Of course you need a strong military threat. There’s no question about that. But if you don’t have tough diplomats, you can’t solve these problems peacefully.

4) Advocate your home country

[Working at the UN] I got to see all sorts of styles of diplomats. There were so many Foreign Ministers that came through, heads of state, and Ambassadors. 193 countries, each having an Ambassador, and I was there for eight years [2001–08]. I saw hundreds of different diplomats – how they interacted with each other, how they made their arguments, how persuasive they were, how persuasive they weren’t, how they were able to articulate the policy. Were they too detailed? Were they not detailed enough? And how they interacted with their staff and with the media. I really got to learn what works, and what a real, good representative of your country looks like. The lesson that I’ve learned: of 193 countries, 192 do not apologize for pushing their own policies. It’s one country [America] that gets in trouble when we put ourselves first – and somehow we’re called radical.

I’ve been in tens of thousands of diplomatic meetings, and I’ve never been in one that doesn’t start and finish with the other country asking America for something. They want something from us – they articulate it, they zero-in on it. They know how to ask.

If you’re going to represent your country, and the taxpayers are paying you to represent your country, you better represent them... You don’t try and represent the country that you’re going to. You’re not going there to talk about how great Germany is. They have their own Ambassador in Washington who is pushing how great Germany is. It’s our job as US Ambassadors to represent America. I became the Ambassador that was unapologetically representing America.

Understanding levers of power:

To be an Ambassador, you have to be able to know how to work the inner-agency process of the US government. You’ve got to be an expert on the US government. Not an expert on giving dinner parties. You have to be an expert on how to maneuver within the US government.

I’m all for using every lever of the US government to make the American people safer.

5) What America First means (and does not)

America First is not just bringing our troops home and putting America First. But it’s getting the allies to do more.

The opposite of America First is consensus with the Europeans.

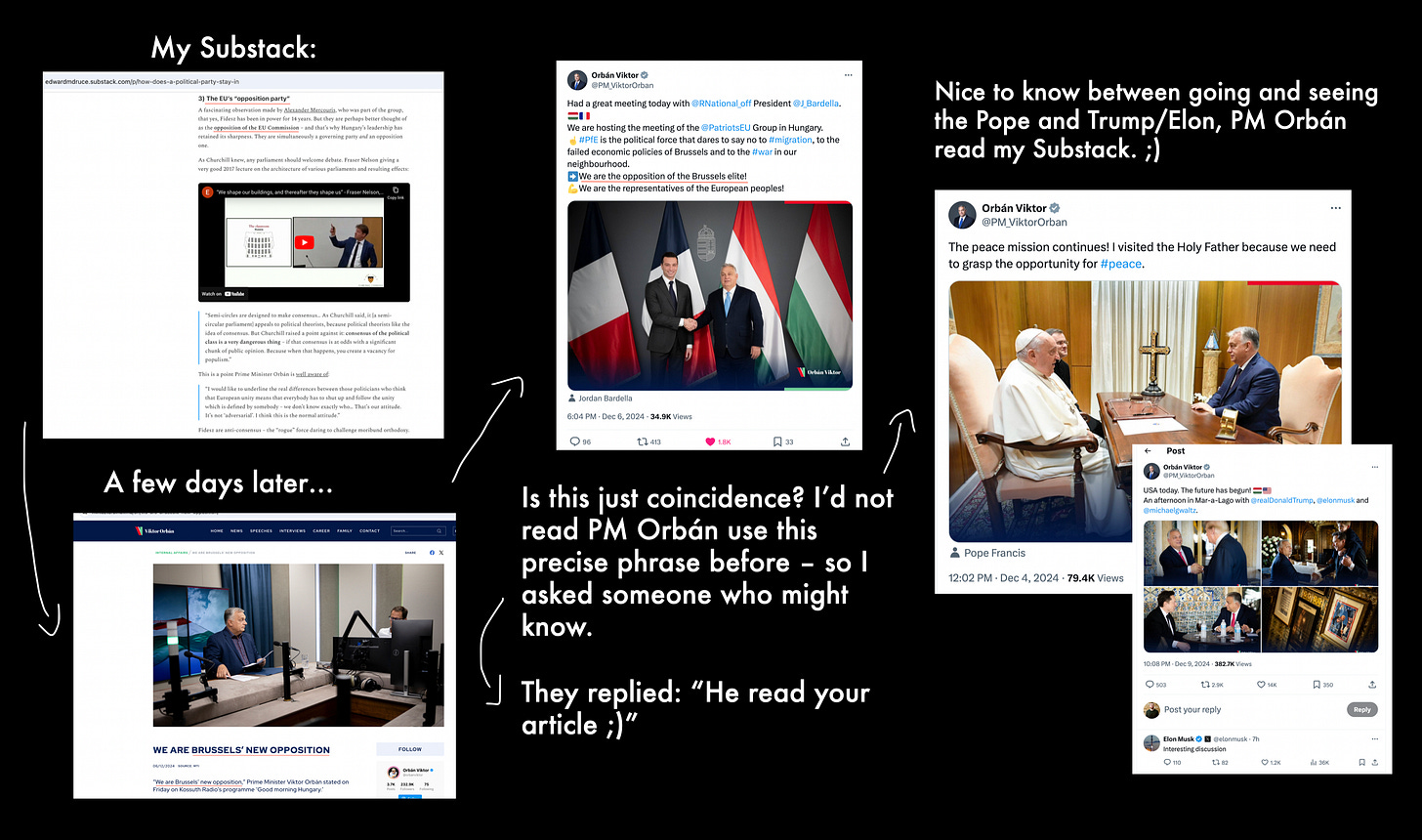

I could not agree more. Two weeks ago, I wrote about this in regards to Hungary, and the need for opposition inside the EU. I’ve been told that Prime Minister Orbán personally read my article, and has actually borrowed a phrase from it: “Brussels’ new opposition”.

America First does not mean America alone. America First does not mean that America succeeds at the expense of others. It means we succeed to the benefit of our people – and by extension, the nations that share our values and our strategic goals.

[In 2020] I spoke to a National Security Advisor of a foreign country, who said to me: ‘I saw your speech. Next time could you add the word multilateral? It would make me feel so much better.’ I said: ‘I get it. America First does not mean America alone. It certainly does mean multilateralism.’ But there’s a difference between… allowing the UN or the Europeans to remake our policy through a consensus process, thereby vetoing part of our US policy because we don’t want to do anything that upsets people. That’s how we got members of NATO not paying their fair share… Many countries didn’t step up because there were no consequences. They just said no. And we were supposed to just keep saying it and not have consequences.

What I believe the Trump Doctrine/America First foreign policy is when it comes to multilateralism is: we decide what our policy is. And then we go and find friends and ways to implement it. We don’t let others veto us – we pull them with us. So there isn’t a stamp of approval… If the UN Security Council wants to endorse our policy, great – we’ll push for it, and we’ll give it a good old try. And we might make some minor changes to it… [But] We don’t go to the E3 [UK, France, Germany] and say: what do you think, and how do we change this? And then it’s an E3+America policy that’s been watered down and turned into jello.

6) Nixon/Kissinger’s “third way” (President Trump is not “isolationist”)

Caught in the tragedy of Vietnam, Americans had split into two ideological camps: those who wanted America to renounce its global leadership, and those who wanted to expand the range of America’s military engagements. It was left to Nixon to find what Henry Kissinger described as ‘a third way’ between abdication and over-extension.

He decided that there was a sound principle that could guide the US in the midst of the Cold War, while reconstructing the public support that was lost in Vietnam. That principle was the national interest. What would have been common sense in most other societies, the national interest was a difficult concept for a people as idealistic as Americans. Americans had long been intoxicated by the belief that the arc of history bends towards justice. That regardless of national histories, traditions, and values, all societies eventually transform into democracies and market economies. Ever since Woodrow Wilson, Americans had grown attached to the idea that the United States should make the entire world ‘safe for democracy’…

But this type of missionary foreign policy makes two costly mistakes. The first is the assumption that all foreign societies must eventually reflect the American model. The second and more dangerous mistake is that American foreign policy does not necessarily need to match our political, military, or financial capabilities. Nixon watched both mistakes lead the United States to a total rupture of social cohesion at home.

In his first annual report on foreign policy, he broke with the tradition: ‘Our objective in the first instance is to support our interests over the long run with a sound foreign policy. The more that policy is based on a realistic assessment of our and others’ interests, the more effective our role in the world can be... Our interests must shape our commitments, rather than the other way around.’

7) No regime change in order to negotiate

For those countries that do not share our values and goals, President Trump is not waiting for the arc of history. He does not make regime change a precondition for negotiations. Instead, the President is determined to outcompete our adversaries. But he’s also willing to cut deals where Americans and global security will benefit. He is incentivising our adversaries to change their behavior, not mobilising to replace them.

8) Speak truth to power

I’m going to live and fight, and do exactly what I think is the right thing to do. I do love to hold reporters to account. They dish out criticism all day, and they freak out when you give them one piece of criticism. They literally are babies about it. And I enjoy that. I actually enjoy showing their hypocrisy and watching them squirm. Because they are not held to account.

I think it’s ruining democracy, when we have a bunch of people who climb up on this mantle and say ‘I am the arbiter of the truth, I am somebody who is going to call balls and strikes’ – and then they don’t, and they are actually advocates. I think it’s shameful, and they should be called out. I think it’s speaking truth to power. If they’re going to dish it out, they should be able to take it.

This time last year, I called out the then most influential editor in the UK (with respect of then-Prime Minister Sunak) on extremely wanting Ukraine coverage, and the deleterious effect on British foreign policy. Many of The Spectator’s own writers wrote to me in robust agreement. Their coverage immediately improved.

We should welcome invitations to insider parties and the like being rescinded in favor of holding influential traditional media to account when it is misrepresenting, or being blind to, reality on the ground.

9) Not a member of the Council on Foreign Relations

I’m not a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. I am definitely an outsider to Washington DC. I think the place is broken. I think the NGO system – when I was at the UN for the US, I managed all the US relationships with NGOs – it’s a jobs program in many ways. They like to have big contracts and money. They like to have events. It’s a system that works for them.

Nothing was more stark about the brokenness of the NGOs and the system in Washington for me than when I became Presidential Envoy for Kosovo and Serbia. There was a collective screaming from the NGOs that covered the Balkans at the time because they said, ‘He doesn’t know anything about the Balkans.’ To which my response was: ‘A lot of you who know a lot about the Balkans for 20 years have never really come up with the right idea – and certainly haven’t moved us forward.’

The entirety of Washington DC think tanks, NGOs, and all those people who write white papers – they had failed for 20 years. But they strangled everybody in my orbit to say: ‘Don’t work with Grenell. He’s not coming to the NGO community.’ All of them invited me to come speak and talk about what was happening, and I just thought it was useless. Because if you’ve tried to work on an issue for 20 years and you’ve failed, maybe we should try something new.

So I came in, didn’t pay attention to them, didn’t pay attention to their politics, and instead went for economic negotiations – and boom, both sides were excited, we met, and we had an agreement.

The Washington DC establishment in foreign policy world just want to control the debate, the issues, and they cannot think outside the box. They are trapped into this thing where they talk about the crisis, they get money and jobs, and they become more powerful in their little NGOs.

So you need outsiders to think creatively. The State Department, unfortunately, is filled with diplomats who are beholden to that NGO foreign policy crowd in DC. I’ve learned that it’s kind of a waste of time to sit around with people who just want to talk about the issues and not really get anything done.

10) Prosperity, not semantics

These stories [the Kosovo-Serbia War] that last 20+ years. What we’ve been able to accomplish here, by pushing the two parties together, is truly historic.

The way that this came about is that the politics were stuck. Everybody knows that. We’ve been fighting and talking about the same thing for decades. They have been fighting about the same symbolism, words, verbs, adjectives – it’s been a nightmare. And what President Trump said to me was, ‘They’re fighting politically about everything. Why don’t we give it a try to do something different and creative? Why not try to do economics first, and let the politics follow the economics?’

That proved actually to be a formula that they were eager for. No one had been talking to them about this.

When I got the two sides together, I said: ‘Look, let’s brainstorm here. How do we move things together? And every single time you bring something up that’s political, I’m going to reject it.’ We don’t need to sit around and get two countries to like each other. This whole idea – this is very controversial – the Europeans love to put all of their eggs in one basket about ‘mutual recognition’ between Kosovo and Serbia. Why do we care if they mutually recognise each other? Really, honestly? If you don’t like me, or I don’t like you… We should [simply] demand that: you have economies that are free-flowing across borders, and growth, and capitalism. And try to get to the point where you have fair trade.

…I’ve said to my friends on both sides: I get that my family was not impacted like your family. I get that I am going to sound very insensitive when I say, ‘Don’t look backwards, look forwards’ and talk about economic growth. I get that you’re looking at me and saying, ‘You don’t know [about all past grievances]’. I totally understand that. But you have to understand that I have value in trying to get you to look to the future. Because your kids don’t just want to sit around and talk about mutual recognition and politics. They want to know that they can stay here because there’s a good job, and they’re going to have a family here, and you’re going to get to see your grandkids because they didn’t pick up and move to a more prosperous country.

So what I tried to do is to say to people: you’ve got to reject this NGO class that wants white papers and mutual recognition, and is sitting around a table and fighting about words. No, that’s not important. What’s important is getting people on a path so they have good-paying jobs and are prosperous and safe.

That is, I think, the theme of what Donald Trump wants to do, and the vision of President Trump’s second term.

11) What happens when you don’t have this

Fascinating fact: Biden/Harris have had to evacuate more Embassies (in panic for shit hitting the fan) than any other administration, ever.

[As a consequence of weak deterrence] We close Embassies, we evacuate. The Biden/Harris Administration has evacuated more Embassies than any other President in the history of the world. It’s terrible.

This is correct. Liberal friends – please take note.

12) De-linking Russia and China

Ric knows Lavrov well:

[At the UN] I dealt with the Ambassador at the time from Russia, Sergey Lavrov. Dealt with him every day – know him well.

(Ric was also in the room when President Trump met with Zelensky in September in New York.)

And:

There’s a really great set of tools to de-link Russia and China. They should not be natural allies. That’s one of the rules I think I’ve learned about foreign policy. Make sure you’re always watching to ensure Russia and China are not ganging up on you.

I wouldn’t necessarily say a ‘wedge’ [that needs driving between the two], but I think that there needs to be a recognition that they [Russia and China] have different goals. They are not natural allies. They have different negotiating styles. They don’t necessarily trust each other – like many people think that they do. And there are ways for us to make sure that our relationship with China is different than with Russia, in a way that it is not America, and Russia plus China on the other side. We can’t have the West versus Russia and China. We’ve seen too many times that’s a bad thing.

...I do think it’s easier than what people think. I know both of their negotiating styles well. I know what they’re like when they come to the multilateral table. I’ve seen them inside the Security Council for eight years. They are not natural allies. They do not prioritize the same things.

Bonus: 13) Live life loud

I do believe people should do public service. You should get a job in Washington DC with an Administration that you believe in. But don’t get trapped into one thing where you just do one thing your whole life. This ride that we call life is so cool and amazing, and you can do a zillion different things. So do it all. Try to go into business. Try to go into politics. Live life loud. I came to that conclusion after I had non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Stage 4, in 2013, and I beat it. I live life with no regrets, and I try to look at all the different things in the world and say – I’d like to do that. Why can’t I pursue that?

*

Watching back some of these interviews (many now four or five years old), I’m struck, yet again, by the prescience of the first Trump Administration. How they got big things right – that were totally taken for granted (or more likely mocked) at the time:

President Trump being extremely firm with Stoltenberg in 2018. Sanctions should never have been dropped on Nord Stream 2.

The remarkable efficacy of President Trump’s sanctions on Iran.

And that all European NATO countries need to step up to 2% defense spending, and beyond.

Ric is one of the most articulate advocates of President Trump’s America First agenda, and has shown consistent belief that President Trump would return to office – unrivalled here by almost anybody. In April 2023, when it seemed to many that DeSantis was hot, Ric with Megyn Kelly:

[I’ve been] Out on the campaign trail, in all of these swing states, listening to voters. If there’s one thing I know, it’s the swing state voters. I’ve been all over, constantly, paying my own way to go and listen, and go to all these rallies and help our candidates on the Right. I have to say that there is no question in my mind that Donald Trump is the nominee. You just have to talk to regular voters. You don’t have to talk to blue checkmarks on Twitter – that’s a whole different conversation! But the activists – there is no possible way they are going for anyone other than Donald Trump.

(This is before DeSantis had even announced, during a moment of maximum buzz about him.) Casting my mind back to April 2023, Ric’s above was not a strongly shared sentiment. This long-standing belief will, I’m sure, now be returned in kind by the President-elect.

I’ll wrap with a line from Demosthenes (343 B.C.): “Ambassadors have no battleships at their disposal, or heavy infantry, or fortresses. Their weapons are words and opportunities.” I wish Mr. Presidential Envoy the absolute best in fulfilling his Special Missions.

PS. Please check out my video, “Diplomacy from first principles: an entrepreneur’s take on geopolitics”. Published in early 2024, it demonstrates extreme alignment with Ric’s thinking, and lays out a blueprint for a new institution – an outcome-oriented Council on Foreign Relations – that would be maximally helpful to incoming US diplomats. “America First’s answer to Foreign Affairs”?

Our prototype site, building this so far: Artofthedeal.org – convenient new redirect. 😉